Desolation Row: the many faces of Ray Carofano

By Bondo Wyszpolski

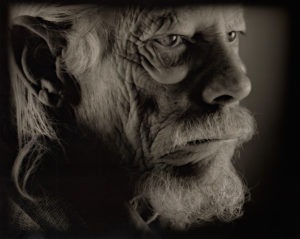

“Phil #2,” from the “Faces of Pedro” series, photographed by Ray Carofano

There were railroad tracks behind the church – and that’s never a good sign. Young Ray Carofano saw older men gathered there, talking, cooking; sometimes they’d hop on a train and be gone.

Carofano remembers going back home and telling his father what he’d seen: “He informed me to stay away from these people; they’re called hobos, and they could be dangerous. Of course, as a child, that made my interest grow even more.”

An only child, Carofano grew up in a town outside of New Haven, Connecticut. His father was a fireman, his mother a telephone operator, and his grandmother lived with the family from the time Carofano was born to, essentially, the time he moved out.

Often he was alone with just his grandmother. “I had to be no more than six or seven years old,” he recalls, “and it seemed like every Friday night someone would come to the back door.” Carofano never saw the person; all he ever knew was that the person was male. Curious, he would ask his grandmother: “Who was that? And she told me he was a man who was homeless or very, very poor; and she would give him food.” What the relationship was between them he never found out.

“That always stuck in my mind. I never got to see the man; she would always say, ‘Go away, go into the living room; I’ll take care of this.’ I don’t know whether it was that she didn’t want me to see somebody down and out in raggedy clothing. I don’t even know what he looked like…”

On another occasion, a caravan of gypsies came into town and set up camp in a small state park. Carofano befriended a gypsy boy of about his age and they rode bikes together. Although theirs was a temporary friendship, he was allowed into the gypsy camp.

“That was another experience that influenced me in my work later on,” Carofano says. “I firmly believe that the experiences that all artists have, from early on up to the present, really have a lot to do with their work.”

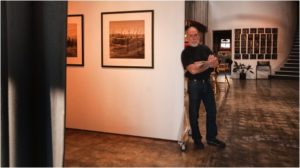

So where has this prelude been leading us? Two places, actually. The first is Rolling Hills Estates, to South Bay Contemporary/Zask Gallery, where Carofano is currently a featured artist and gives a talk this evening, Thursday, Jan. 30, from 7 to 8:30 p.m. It’s also leading us to his own venue, Gallery 478, in San Pedro, which will be open next Thursday, Feb. 2, during the city’s monthly First Thursday Art Walk.

Depleted

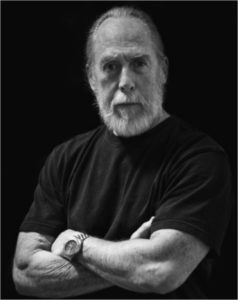

Ray Carofano. Photo by Gloria Plascencia

There are two ongoing projects that to a large extent define Ray Carofano, the photographer. One of them, and I’m simplifying, is comprised of portraits (aesthetic headshots, to put an actor’s spin on it) of often marginalized men and women who live in or who have wandered through San Pedro. The other is of desolated towns, the detritus of civilization. Despite the subject matter, one realizes that both series dovetail and complement one another.

“Why do I point a camera at a homeless person and want to take his photograph,” Carofano says, “or [photograph] a dwelling in the desert that’s been turning back into the earth? The desire to do that comes from my childhood. Not only from my childhood, it comes all the way up through school, the people I met in school, the peer groups that I hung out with; all these experiences [constitute] who I am today. And I think that really holds true for everyone. Everything that happens to you is what ends up being your personality.”

“The Land of Broken Dreams” is a series of photographs that were taken in the desert, and a selection of large-format prints from this body of work is currently hanging in Carofano’s gallery/studio. We see vistas of emptiness, and we see the remains, the carcasses, of abandoned homes or vehicles. What we don’t see are human beings – even the hobos avoid this place. Despite this, Carofano says, “I believe [the images] tell more than if I had taken a portrait of the people that live in those dwellings in the desert. If you look at it you can see their lifestyle, how they lived, where they lived.”

In the latter 1960s, when Carofano was about 23 years old, he went to the Bowery in New York City and photographed people living on the sidewalks, sleeping on the sidewalks, passed out on the sidewalks or in doorways. Those photographs are different in one crucial respect from the “Faces of Pedro” series in that they are not tight shots. They show the viewer the luckless person’s clothing, belongings, or the patch of dirt or concrete around him. Although these things confirm and supplement the subject itself – a man or woman going through hard times – they reinforce a stereotypical response while allowing us to evade a one-on-one, face-to-face encounter with the specific individual. “The Faces of Pedro,” however, cuts out all that extraneous detail and forces us to confront each man or woman as a human being like ourselves.

The invisible man (and woman)

Ray Carofano in his gallery, with images from “The Land of Broken Dreams” to the left and “Faces of Pedro” on the far wall behind him. Photo by Gloria Plascencia

“There’s a saying,” Carofano continues, “and I think a homeless person said this. It goes something like, ‘Love me if you can, hate me if you will, but for God’s sake don’t ignore me.’ Powerful. Think about it. And this is what I’m talking about. People ignore the homeless. They don’t want to look at them, they want to make believe they don’t exist.

“We all have needs and desires,” he adds. “Their needs and desires are different than the average person. Theirs are about survival. One of our friends might say, ‘Well, I’m gonna get a new iPhone.’ Their needs are very basic. Their needs are shelter and food.”

Right now, Carofano is livid about a new ordinance, 8602, that would “make it illegal for anyone to be living or sleeping in a vehicle of their own on L.A. streets, in L.A. parking lots, or on any land that the city owns. I find it absolutely disgusting. It’s just another strike at the homeless… I can only imagine how many people today are living in vehicles, and what are you gonna do? Throw them out now? It’s up to six months in jail if you get caught and they can impound your vehicle. I mean, what else can you do? Just take them out and shoot them? It’s horrifying, man.”

Homelessness may not seem like an apt subject for the arts section of your newspaper, but it has and keeps on informing the content of Carofano’s work, culminating – more specifically, as we will see – in the “Faces of Pedro” series.

“I grew up in a town where there weren’t very many homeless people. That whole homeless thing back in the ‘60s, ‘70s, probably all the way into the ‘80s, was driven by scarcity, meaning there wasn’t enough food or maybe enough shelter for them; and today it’s driven by an entirely different situation. Today we’re talking about over-producing, massive consumerism.”

He mentions Venice, a few miles up the coast from us, as an example of the gentrification that has pushed the poor (the bohemians and the artists, too, for that matter) away from the coast, and away from the stagnant canals that were a reminder of better days and bigger dreams. The area was cleaned up, expensive homes were built, and wealthier residents moved in.

“As people get up [economically] like that they don’t like to see people homeless. They don’t want to see people sleeping in cars outside their house. It makes them nervous.” If you’re that poor, you’re also powerless; and powerless also to prevent ordinances and codes that find ways to ban you from the very streets where perhaps you once lived.

“I observe homeless people,” Carofano says. “I have for years and years. When I see them I look at them. If I have the time I have a conversation with them. The average person,” he says, just looks the other way.

From revelation to passion

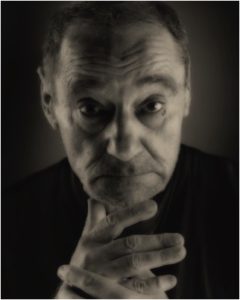

“Harold Plople,” from the “Faces of Pedro” series, photographed by Ray Carofano

Ray Carofano finished up at Connecticut State with a Bachelors in Liberal Arts. Although photography was in his mind, he wasn’t sure what occupation he wanted to pursue. Maybe business, he thought. Working at a brokerage firm in New Haven, he contemplated becoming a stockbroker. But one day, out on his lunch break, he passed a magazine stand and spotted an issue of “Popular Photography,” and not just any copy but the annual roundup of the year’s best work.

“As I went through that publication I realized for the first time the potential for self-expression and that photography is really an art form. This opened up a whole new window and I realized that I really wanted to be a photographer.”

In the latter 1960s (he was born in 1942), Carofano moved to California and worked in a photography store in Redondo Beach. One of his co-workers, Emilio Mercado, seems to have been a mentor of sorts, who helped him perfect his art. Although Carofano moved to his current location in 1997, he maintained a studio in Gardena for 25 years.

Gallery 478 in San Pedro is both a studio and a home, where Carofano lives with his wife, Arnée, who is also a photographer although in a much different style. Of course, she is much more than that, as anyone who knows the couple will attest. As her husband says, “Without her I don’t know where I’d be. She helps me in every possible way.”

Many people, by the time they reach their 60s, begin to think of retirement, and of slowing down. Having interviewed hundreds of them, I don’t believe that artists think that way. In fact, as they age, they often put in longer hours, and Carofano says it’s easy for him to work 10 or 12 hours a day. “Because I work for myself I’m a pretty hard cookie when it comes to the boss. I push myself probably more than I should, but it’s something I enjoy. It’s my passion.”

That isn’t to say he’s out in the desert or in his studio and photographing every day. A couple of months may go by without Carofano using his camera, but in that time he may be printing, he may be reading photography books and discussing art, or he may be planning an entirely new body of work. Eventually, the desire to pick up his camera is uncontainable:

“When I reach this stage my visual senses seem to sharpen,” he says. “That’s what photography is all about anyway, it’s about seeing. Not only with the eyes; it has to do with feelings, too. When it reaches that level I’ll start photographing again. Then the process starts all over.”

A disappearing breed

“Salem Girl,” from the “Faces of Pedro” series, photographed by Ray Carofano

After moving to California, Carofano often headed down to Skid Row in Los Angeles and photographed the homeless in their environment, just as he had years earlier in the Bowery. “But the idea I had here was to bring them into the studio, (to place them) against a neutral background, and photograph their faces close up.”

“The Faces of Pedro” is on display as a kind of collective installation piece on one of the walls of Carofano’s gallery, each one roughly eight by ten inches. The small selection now on view at South Bay Contemporary/Zask Gallery is comprised of larger prints, and in these extreme close-ups we see the lines in each face and the story in their eyes.

Carofano’s ideal venue for viewing these faces would be a tightly enclosed space, “almost in a hallway,” he says, “where you can’t back up and look at them from a distance. You’re actually forced to look right into their eyes up close.”

The reason why is simple:

“I’m trying to make them real. I’m interested in recognition for these people – I want them to be recognized and I want people to know what’s going on in America today, in the City of L.A.”

Why these particular people, and how did he find them?

“It wasn’t long after moving to San Pedro that I realized the faces that were in this town were like faces I had not seen before [and] were so interesting to me that I wanted to photograph some of them.” However, the project never set out to be solely about the homeless. “What I was looking for were just really interesting faces. But, as it happened, a majority of them ended up being homeless people or people on the edge of society. Back in those days I found them by going to a couple of bars where they hung out, rather sleazy bars.

“I had conversations with them,” Carofano continues, “maybe shared a couple of cold ones with them, and talked to them about the project – which I was simply calling ‘The Face of San Pedro.’ I was telling them that it’s about the history of San Pedro, which it is, because these faces tell a story about who they are and what they do. Getting them here (the studio), into a strange place where they hadn’t been, was a little harder. Some people were all for it right away; other people it had actually taken me years.” New York Peter, for example, had to be courted for three years until he agreed.

Even so, Carofano says, “Some people said ‘No, I don’t want it.’ Maybe dignity, and so forth. The homeless people I would offer some money, so they got paid rather well for their time. And not all of them are homeless; some of them are artists. Some of them are old and retired, but they have some kind of pension and don’t need the money. But people in need I would help.”

One of the most distinguished people in the series is the late artist Harold Plople, who had as difficult a life as one might imagine, but ended up being adored as a person and praised for his work – not by just one or two friends but virtually by everyone who ever got to know him. He was humble, generous, childlike, had an astonishingly deep and divergent interest in philosophy, religion, pornography, literature and art, would spend his money on books, and – I can’t put this any other way – had saintly qualities. Yet he too had been homeless, had lived in halfway houses and battled drugs and alcohol, and most people would not have looked him in the eye if they’d seen him on the street. He was, perhaps, our Van Gogh. You can see his portrait at South Bay Contemporary/Zask Gallery, and you can see many of his works there as well.

Before all is forgotten

“There’s a story behind every one,” Carofano says, as we look over the “Faces of Pedro” on the wall behind us. “I could tell you probably at least 15 minutes on every face up there because of the conversations I’ve had with them. Spaghetti Eddie – they all have great street names – was a boxer and a bank robber in his early days, spent time on a chain gang in Georgia and escaped, and got back to New York only to be caught again.”

This series is a work in progress and Carofano doesn’t rush it. Some projects dictate the terms, it’s that simple. But he’s always prepared for the next shoot, the next interesting face.

“Everything’s ready, so that when I find somebody all I have to do is get them in here. There’s a blue piece of tape on the floor. They stand on the tape and off we go. There’s no direction on my part other than they need to stand on a certain spot. And that’s it.”

While he and his subject talk, Carofano begins to press the shutter, and another piece of history is documented, and then preserved for a future time when everything we know has changed and none of us are here to remember the way it was.

Ray Carofano talks about his work and his creative process Thursday, from 7 to 8:30 p.m. at South Bay Contemporary/Zask Gallery, located in the Promenade on the Peninsula, 550 Deep Valley Dr., #151, Rolling Hills Estates.